With the kind permission of Arlene M. Katz and Sheila McNamee

Arlene M. Katz and Kathleen Clark, with Elizabeth Jameson

“Join me in trying to create spaces for conversation;

How can we all create spaces that allow for conversation?” (EJ)

“Listening to the afflicted is not merely moral praxis, although it is that.

It affords us rich insights.” (Farmer and Gastineau, 2004)

In this chapter we invite the reader to enact a form of participatory dialog with one of the au-thors (EJ) as she reflects on her illness experience with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and her life as lawyer and artist, while navigating healthcare. Using methods of social poetics (Katz and Shotter, 1996), we begin by noticing what strikes us. We then articulate these striking moments in dialogue with each other, making visible what matters to us. We carry this over into new possibilities of engagement and practice. We juxtapose and intertwine the uniqueness of EJ’s articulated lived experience with the words of other authors who have reflected on social construction and relationality. Our attempt is to make visible what matters in healthcare and the experience of illness. To that end, we focus on relational engagement with professionals, on acknowledgement, sacred spaces, care and caregiving, and on what can be carried over into other practices. In effect, the chapter aims to serve as an exem-plar of relationality and social construction and, in the writing, a poetic enactment of it.

Here, we navigate the world of healthcare and the world of the lived experience of health professionals and patients; the one emphasizing time constraints, ‘efficiency’, fixed analytic catego-ries, and a push for consensus, the other the world of illness experience and social suffering. We introduce participatory dialogic inquiry – a form of social constructionist practice – into a healthcare setting. We privilege the voices of patients and community members which are often unheard or silenced and notice how new possibilities of meaning and engagement emerge. Hearing the voice of the patient can teach all of us how to treat, include, learn from and be guided by them. Practitioners may be surprised, shifting assumptions, as they enter into different worlds of meaning and possibili-ties. We navigate what matters to each in this emerging local moral world (Kleinman, 2012).

In the following pages, we present an ‘exemplar’ in dialogue with one of our authors EJ, of how illness, disease, and imperfection can be transformed by creative art, teaching, thinking, and sharing. As co-authors, we reflect on how community members, patients, health practitioners, train-ees and healthcare leaders are invited to engage in mutual inquiry, and became co-teachers, co-learners and co-researchers. Using poetic reflection and dialogic inquiry, the authors (acting here as participants) articulate their lived experience of health and illness, care and caregiving. In so doing, they make visible what really matters to them, illuminating their practices from within, shifting as-sumptions, and exemplifying the wider issues of disparities.

We are invited into different worlds from the impact of diagnosis and continuing on with the lived experience of a chronic illness, moving beyond fixed categories to an ongoing relational process. By inviting the reader to navigate the multiple voices of patient, clinician, and caregiver, we are issuing a call to acknowledge what is at stake for each of them and re-socialize what are commonly seen as fixed categories into processual events. New possibilities can emerge in the space between the actors, shifting from the stance of an outside observer to that of participants, creating new meanings, and making visible what might otherwise pass by unnoticed. We notice the shift from feeling ‘acted upon’ to becoming an actor, from a sense of isolation to one of connection and participation.

The Waiting Room

The setting is all too familiar—uncanny in its familiar unfamiliarity—the subspecialty waiting room. EJ has seen many of them and has long thought about how they could be transformed. In contrast to the awkward silence, she would invite all waiting patients to share their thoughts and feelings.

The importance of specialty waiting rooms… a chance we can see one another… at-tempt to create community, attempt to define our tribe. Typically, in the waiting room, there is just one large video monitor, nothing else… (a) continuous loop of National Geographic baby animals. My question is, is that helpful in defining your new community?

The community is one of patients and their caregivers. They are a community because they are facing the lifelong challenges of progressive disease. One of the key aspects to becoming a community is to recognize each other and create the possibility to talk whenever we are in the same room. People with lifelong, long-term illnesses return to the same waiting rooms, over and over and over. Talking together is beneficial to prevent or reduce loneliness and profound isolation.

EJ paints a not unfamiliar scene—the waiting room as the space of otherness, the paradox of strangers in a shared space. Seemingly isolated monads, fiendishly exploring their mobile phones, flipping through magazines, TV screens flashing endless programming. Implicitly she asks, “Do we dare acknowledge each other?” And she adds, “Not acknowledging can lead to unfounded fears, biases and self-hatred.”

We are in the ‘silent world’ (Katz, 1984) where “in this gesture of waiting, I allow the knowledge of the other to mark me” (Das, 1998). EJ was moved by this and wondered from her own experience whether the answer might lie in “patient-led design to take control of our healthcare en-vironment, as without listening to patient input and consideration it is impossible to have a waiting room space that is in the best interests of the patient or the staff. In my soul, I want to be an activist in terms of helping people.”

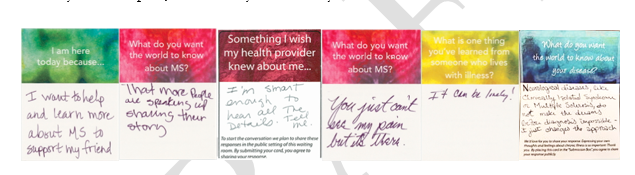

EJ demonstrates how she moved from being ‘struck by’ her experience, making visible what matters and carrying it over to a new practice: one day she began inviting those in the waiting room to engage in conversation and later she offered them the possibility of reflecting on ‘conversation cards’ posing questions such as

• What is the impact of the disease on your life?

• How would you describe your illness?

• If you were a poet, how would you describe your disease?

Some of the more striking reflections included:

Q: What do you want the world to know about Multiple Sclerosis?

• That more people are speaking up, sharing their story.

• Learning to live with MS is like learning to ride a surfboard.

• You just can’t see my pain but it’s there.

• Neurological Diseases like Clinically Isolated Syndrome or

Multiple Sclerosis do not make the dreams after diagnosis impossible.

It just changes the approach.

Q: What is one thing you’ve learned about someone who lives with illness?

• It can be lonely.

Q: I am here today because…

• I want to help and learn more about MS to support my friend.

• MS can be an extreme weight on a person.

• The more support, light and recognition of and for the disease, the better.

In our conversations, EJ reflected on her waiting room project: “These moments of connection are about acknowledging illness in all its forms, creating new, positive experiences, and offering an alternative to the awkward silences in the clinical setting. There is a sense of pride, or togetherness, when we honor our own thoughts and feelings. And to share these thoughts and feelings in such a vulnerable place as the clinic waiting room is empowering for all” (Jameson, 2018).

Illness Experience

EJ recalls the shifts in her life as she began to experience physical symptoms, and then the di-agnosis of MS. We contrast the act of diagnosis as determining a fixed category, to one that is social-ly constructed, co-created from the emerging meanings of participants. Rather than presuming meaning for a person, we are concerned with how we make meaning with them in our interactions. This contrast is a key aspect of a relational process, which takes into account what is at stake for the person of the patient as human being.

When I was first diagnosed with MS, I experienced aphasia and complete lack of speech. When my speech returned, I still had problems with word-finding; it was embarrassing as a courtroom lawyer, and I realized I needed to make a shift in careers. I had an existential crisis, because I still wanted to do something meaningful. I eventually transitioned from being a pub-lic interest lawyer to a public interest artist… feeding my soul.

EJ experienced a series of ‘existential crises’, having to give up the practice of law, in service of others, especially using her voice to advocate for voiceless children both in and out of court. In her drive and ambition to create meaning from her disease, she discovered a new way to communicate through painting and etching, two art mediums which she had never engaged with previously.

I tried to put the pieces back together that were blown by this tsunami… ongoing struggle… The mess, chaos of illness; its depression, learning to cope… Yet, thinking all the while, how can I be of service to others?

Her newly found practice as an artist allowed her to transform the medical technology that sur-rounded her (e.g., her MRI images which seemed to define her as a person living with a diseased brain) from the sense of being treated as an object to that of a participant. It “taught me to take ownership of that MRI, be friends with that MRI; make it beautiful, complex.” She resolved to try to humanize her MRIs for herself and others by making them beautiful and interesting, wanting these transformed images to serve as a starting point to describe her ever-changing experience of living with a progressive illness. These unconventional self-portraits invited researchers and clini-cians to see their work in a new context, reshaping how patients might come to terms with their disease. In so doing, there was a shift from the fixity of the medical image to entering into a dialogue with it—a transformative engagement. EJ took back the medical technology and allowed it into the patient’s living room.

EJ: I had the black and white MRIs in a corner of my office.

They were ugly and terrifying.

I decided to make MRIs more human…

so that hopefully someone could see me, and not just the data.

Confront them with kindness and humanness.

What was originally daunting

Is still daunting.

I got up close and personal with the brain and brain disease.

I love technology. I fell in love with revolution around technology.

On reflection, what I really fell in love with is the re-discovery of myself through technology.

This resonates with the words of John Berger, who stresses the need to re-find hope: “… an horizon has to be discovered. And for this we have to re-find hope – against all the odds of what the new order pretends and perpetrates. Hope, however, is an act of faith and has to be sustained by other concrete actions… This will lead to collaborations which deny discontinuity” (Berger, 2001).

Navigating Multiple Descriptions: Human Being and Disability

EJ is embodying a way to go on, echoing Wittgenstein (1953) who famously asked, “How do we go on together?” She offers a new way for patients to see themselves and their brains. It is a new vocabulary for scientists and medical professionals inviting them to listen to the patient, to listen to how the patient defines how illness impacts their lives. It is also a new vocabulary for patients and family members, offering new ways to express themselves. Learning new language is important to facilitate the best, most efficient and respectful answers and solutions.

Speaking to an audience of healthcare professionals and students, EJ was asked how she re-mains motivated. She mentioned her blog and her shift to writing the personal essay as narrative and her desire to share her story in as many places as possible, including publication in the New York Times and British Medical Journal (BMJ). She characterizes her life with progressive MS as a ‘shit show’, filled with difficulties and constant transitions and definitions of who I am. She also talked about her transformation as artist: “What can I create, helping myself and the medical com-munity? … I’m a human being…” She expressed what matters to her in poetic form:

I treat my disease as a colorful bird that lives on my shoulder,

and I want to love what’s on my shoulder.

It’s always going to be there.

And some days it’s biting me, sometimes it’s drawing blood.

Sometimes it’s cooing.

Be respectful of the bird.

It’s always there. It’s me.

I want to love me.

So I say look, I have a bad disease but it’s part of me.

It’s on my shoulder.

So, make friends with it.

Love it and move on.

This is my quiet, internal dialogue where I can find something beautiful and less lonely about my experience with illness. If people in the waiting room could share their thoughts and feelings, then perhaps I could learn from others how they deal with their diseases, and therefore that would lead to some form of community and not just me with my ‘bird’.

John Berger would have agreed. “Poetry makes language care because it renders everything inti-mate… There is often nothing more substantial to place against the cruelty and indifference of the world than this caring” (Berger, 2001).

Relational Engagement with Professionals

As we have seen, EJ embodies a way of opening new possible meanings and (inter)actions in the patient-physician encounter. Her ability to speak continues to diminish slowly and she wants to talk with her physician about how this terrifies her but wonders how. By offering her own experi-ence to illuminate what she’d like people to know about disability, there is a shift for those being treated as ‘object’ to ‘subject’, to being known as a human being. We continue our conversation with her and ask what is most important for people to know about disability?

EJ: What does it mean to be losing control?

(There are) all sorts of disabilities.

It’s fascinating. I love looking at all types of medical technology.

I like being part of the process.

I don’t want to be subject to the process, the years of illness.

I want to be on top of it.

I want to have meaningful conversation with physicians.

Q: How do you create a meaningful conversation with physicians?

EJ: First, meaningful conversations with yourself,

then, meaningful conversations with others.

I’m struck by how many people…they don’t want to hear about your disease.

I want to be proud of my disease.

There’s a bird on my shoulder.

I want to respect the bird.

I want my friends to ask about the bird.

How to find my tribe.

I find members of my tribe.

I like people to not be afraid of illness.

I want a world where people realize we’re ill, going to die.

It’s not socially acceptable to talk about illness.

References

Berger, J. (2001) “The hour of poetry,” in John Berger Selected Essays, G.Dyer (Ed.), NY:Pantheon.

Berland, G. and Buckwalter, G. (2008) NPR Interview with Gretchen Berland and Galen Buckwalter on video recording and revelations about interactions between physicians and patients with disabilities. NEJM Audio Interview, doi:10.1056/NEJMdo002136.

Berland, G. “The View from the Other Side: patients, doctors and the power of a camera”, doi:10.1056/NEJMdo002136, December 20, 2007.

Cavell, S. (1996) “Comments on Veena Das’s Essay ‘Language and Body: Transaction in the Constructions of Pain’,” Dædalus, 125 (1), pp. 93-98.

Chodosh, S. and Tormes, L. (2016) “The Art of Neuroscience”, Scientific American, in SA Mind 27,6, 52-56. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind1116-52.

Das, V. (1998) “Language and the Body: Transactions in the Construction of Pain,” Dædalus, 125 (1), 67-92.

Gergen, K.J. (2009) Relational being: beyond self and community, NY: Oxford University Books.

Jameson, E. (2018) “I wish my healthcare provider knew…” thebmjopinion, January 22, 2018.

Jameson, E. (2018) “Dreaming of a Prettier Chair”, New Mobility, April 2, 2018.

Jameson, E. (2019) “Imperfect Life Art Show at KECK School of Medicine at USC,” April 17, 2019 “https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6S9nDWgmqr4”.

Katz, J. (1984) The Silent World of Doctor and Patient, NY:The Free Press.

Katz, A.M., and Alegria, M. (2009) “The Clinical Encounter as Local Moral World Shifts of Assumptions and Transformations in Relational Context,” Social Science and Medicine 68: pp. 1238–1246.

Katz, A.M., Conant, L., Inui, T., Baron, D. and Bor, D. (2000) “A Council of Elders: Creating a Multi-Voiced Dialogue in a Community of Care,” Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 50(6), 2, pp. 851-860.

Katz, A.M., & Shotter, J. (1996) “Hearing the Patient’s ‘Voice’: Toward a Social Poetics in Diagnostic Inter-views,” Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 43, No. 6, pp. 919-931.

Kleinman, A. (1995) Writing at the Margin: Discourse between Anthropology and Medicine, Berkeley: U.Cal. Press.

Kleinman, A. (2012) “The art of medicine: Caregiving as moral experience”, The Lancet, Vol. 380, November 3, 2012, pp.1550-1551.

Kleinman, A. (2015) The Art of Medicine, “Care: in search of a health agenda”, The Lancet, Vol. 386, July 18, 2017, pp. 240-241.

Radley, A. and Bell, S.E., (2011) “Another way of knowing: Art, disease and illness experience,” Health, 15(3), pp.219-222.

Vilela e Souza, L, Santos, MA, Medonca Corradi-Webster, C., Guaneas, C., Moscheta, M. (2010) “Social Con-struction and Health: An interview with Sheila McNamee”, Universitas Psychologica, vol 9(2), pp.574-584.

Wasserman, IC and McNamee, S. (2010) “Promoting compassionate care with the older people: a relational imperative,” International Journal of Older People Nursing, 5, pp. 309-316.

Wittgenstein, L.W. (1953) Philosophical Investigations, Oxford: Blackwell.