With the kind permission of Arlene M. Katz and Sheila McNamee

Arlene M. Katz and Kathleen Clark, with Elizabeth Jameson

“Join me in trying to create spaces for conversation;

How can we all create spaces that allow for conversation?” (EJ)

“Listening to the afflicted is not merely moral praxis, although it is that.

It affords us rich insights.” (Farmer and Gastineau, 2004)

Sacred spaces

As EJ sought to find her community, ‘her tribe’, her loneliness was transformed into sharing ‘sacred spaces’ with others—a sense of the ‘silence of a cathedral’; of being open, touched, noticed, moved. In her words, “it served as an invitation for others to see that I accepted being vulnerable and naked. My brain was put on view”. Honoring a lifelong commitment to social justice now in-cludes relational justice as a way to create sacred space. It is this act of co-creation with others that is sacred, this shift from taken-for-granted assumptions to creating new possibilities for engagement and knowing. The act of being acknowledged in the space between one and another, a felt sense be-yond a particular physical space, can create new meaning and possibilities. To acknowledge, to ‘walk with’ another, is a relational process, an attunement to what matters most to each actor. It can trans-form the space between them into a sacred ‘liminal’ space.

As EJ articulates what she is moved by in dialogue with us, she makes visible what matters, which can often go by unnoticed, and how it can be carried over into practice. We explore the rela-tional domains of Acknowledgement, Care and Caregiving.

Acknowledgement

EJ: “My goal is to find the disease, the illness, the person… to not avoid them.

A goal is to like our bodies and get rid of the idea of perfection.

We’re all human beings.

Q: It’s not any one disease.

EJ: It’s imperfection…

To accept, honor and find beauty in the inevitable problems of being human.

It includes disease, illness…

Connection and disconnection in daily life

Some of my best friends don’t ask me how I am.

Nobody asks me.

Often I don’t need to talk about my illness but it’s nice when people ask.

That’s why I feel lonely.

I wish someone would ask if my disease is quiet…

Q: What’s in the word acknowledgement?

EJ: Not invisible.

It’s like I’m nine months pregnant and nobody asks when the baby is due…

If acknowledged, it’s not invisible, not silent.

As we listen, EJ’s words make visible to us what matters to her:

EJ: All my life, it’s been so important for me to be doing something interesting.

I want people to feel that what I’m doing in my life, despite my illness, is interesting; more im-portantly, meaningful both to myself and to disenfranchised people.

What can be carried over into practice…

EJ: I want physicians to feel their patients are interesting,

to have an interesting, fascinating disease…

to see us as a whole person,

and how we deal with our daily challenges that are perpetually changing:

Ask how the disease affects the patient’s loved ones,

how simple daily habits (for other ‘non-disabled’ persons) become a time-consuming

puzzle to decipher.

Make the daily struggles visible.

Acknowledge the complexity.

Physicians can’t solve the problems, but can acknowledge…

They can say, ‘wow’…

From which we see that it is much more than just the disease, it’s the responsiveness to what is at stake in ordinary life. Acknowledgement here is a moral imperative, echoing Kleinman’s (1995, p.117) warning that, “We, each of us, injure the humanity of our fellow sufferers each time we fail to privilege their voices, their experiences” instead, “…You are forced to respond, either to acknowledge it (pain) in return or to avoid it; the future between us is at stake” (Cavell, 1996).

The Silent World

Struck by a recent encounter with her doctor, which recalls Jay Katz’ seminal work on “The Silent world of Doctor and Patient” (Katz, 1984), she offers:

EJ: With MS, there’s nothing you can do.

At my stage, – the progressive loss of the usage of my arms and my legs to the point of quadriplegia, and now my voice – and experiencing the failure of 30 years of various treat-ments…

there’s nothing to be done at this time.

My neurologist said, “you can come all the time

but there’s nothing I can do; stay home and watch movies.”

She then reminds us what matters:

But you can witness me,

Acknowledge my current life and find it interesting, not scary.

In her award-winning film Rolling, physician Gretchen Berland partnered with three participants in wheelchairs, giving them cameras to capture what mattered to them. The results moved her as it “revealed a world that I had no idea existed.” In reflecting on what doctors might take away from the film, she reminded us of what is at stake for us as human beings,

At some point in our life, everyone is going to be vulnerable. That’s the nature of being a human being. And most people will be vulnerable with their health care provider… And when you are, at that moment in your life, you really hope that the person you are talking to and asking for as-sistance is caring and looking at you as a human being. And there are many times in Rolling where it was clear that the health care system was not… disability is not all about hardship. More than half of what the three participants filmed was about identity and the definition of a person. (Berland, 2008)

In contrast to how the language of the medical system often defines people, perhaps understandable in that context, Berland (2008) emphasizes that

We have to make sure that we also remember there’s a person behind that too. Listening is really an art. Listening to what someone tells you is not easy to do, what someone is really telling you in an exam room. Asking the question in such a way that the patient can tell you what’s going on.

Care and caregiving

Both family (EJ and her husband) and professional caregivers talk movingly about the experience of caring. EJ says that, “you discover ways to be, illuminate what had not been noticed, or had been taken for granted, like feeding…” A whole world opens up… making visible what would otherwise pass by unnoticed. What matters, Kleinman (2015) reminds us, is that “Care is relational and recip-rocal” (p. 240). What follows are comments from her caregivers both at home and at a presentation to medical providers (Jameson, 2019):

Caregiver 1

…I learned things I never thought about…

It’s like when I travel to strange places.

It’s completely illuminating…

Not just caregiver…

When we work together (writing and editing), we’re looking for the universal thread, not just disability.

Caregiver 2

It’s an absolute privilege to love this beautiful soul. She has an amazing heart to share her gifts with the world and to see how this body… and how it is doesn’t stop her from being loving, giv-ing her very best to everyone in the midst of being fed and bathroomed. In the highest and low-est part of your life, still find the joy and the beauty in it.

For me and the caregivers, if you have the opportunity to be with another human being, serve them at your highest capability of love, you have blessed the world in this life.

Caregiving becomes a sacred process, resonating deeply between caregiver and receiver. Each is changed in the process. Kleinman (2012) emphasizes the “moral face of caregiving” not only its rela-tional nature but as a moral imperative.

Acknowledgment of the personhood of sufferers and affirmation of their condition and struggle have long been recognised as the most basic and sustaining of moral acts, whether among the friendship and kin network or in patient–physician and other professional relationships. (p. 1550-1551)

This is indeed a call to presence.

… being there, existentially, even when nothing practical can be done and hope itself is eclipsed, as central to the giving of care. And it is also important in care receiving, because caregiving is almost always a deeply interpersonal, relational practice that resonates with the most troubling preoccupations of both carer and sufferer about living, about self, and about dignity. (ibid.)

Kleinman raises the important question as to whether today’s biomedicine and caregiving are in-compatible, given privileging market forces and efficiency. He calls for

a serious discussion about caregiving and a reconsideration of its place in medical education, medical practice, and medical research, on the one side, and its significance for patients, families and communities, on the other.

The great failure of modern medicine to promote caregiving as an existential practice and moral vision. (ibid.)

Carrying over into other practices

Our stories of illness and where we can listen to our stories, tell stories, listen to stories, learn from each other: hopes – the hope develops further empathy for people’s illness and disabili-ties. (EJ)

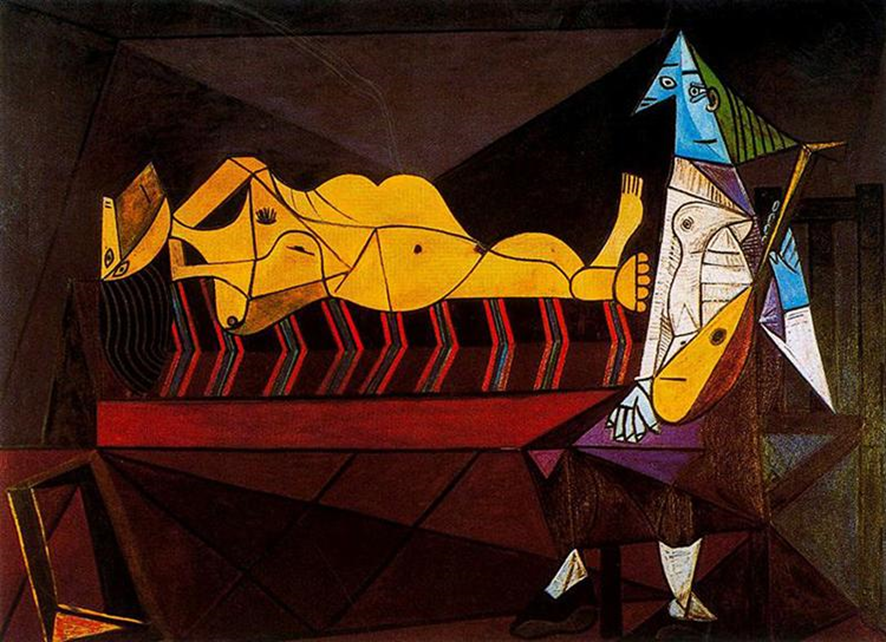

Artworks also tell about illness experience and are used as claims to social justice (Radley and Bell, 2011).

What can we take from these experiences, beyond MS, beyond disabilities, to improve caregiv-ing and acknowledge human suffering? We can carry forward EJ’s words as well as her extensive work in lightening the suffering of others, by placing her mission in a wider context, the context of caregiving for the suffering. Her art invites social engagement in the space between society and dis-ease, between science and art, to change the narrative of illness, aging and disability and to get peo-ple thinking and talking about life with disease. Her work makes the invisible visible in a hopeful, graceful way. It connects us all.

As her mobility has lessened and her voice has grown fainter, her art has become her voice. Now confined to a wheelchair, she is aware of people moving away from her, and recalls her own prior feeling that anyone in a wheelchair is really scary and unapproachable. To counter this, she now uses her aesthetic sense to encourage wheelchair manufacturers to design wheelchairs that are open, approachable, and welcoming:

The external parts of my wheelchair inform how I am perceived, how I take up space… It is the very first thing I feel every time I interact with another person. I want my chair to be… a conversation starter instead of an intimidating machine. (Jameson, 2018)

We invited EJ to reflect on advice to professionals.

Q: How would you like residents to learn about acknowledgement and sacred space?

EJ: Residents (can) learn about acknowledgement and space.

Absolutely.

Each patient has a different relationship with “the bird”,

the way to deal with illness and disability.

Take the time to try to empathize and understand.

Empathy can’t occur without asking patients

how the disease impacts their daily life.

Q: And students?

EJ: Encourage medical students to embrace what you’re doing and know how hard it is and how much joy can be in your profession. But it has to be in communication with the patients… Don’t be afraid to ask questions. That is so critical to not have siloes. I’m so delighted to talk to you about ways we can work together to open up the silo…

Q: What would you want to say in medical schools?

EJ: Do not be afraid of talking about the good, the bad, the ugly…

the beauty, the boring, of life with disability.

Do not try to avoid being uncomfortable –

because that doesn’t allow the person to be fully seen.

Be present even if it is uncomfortable.

Q: Beyond MS to chronic illness

EJ: The idea of discussing it with appropriate language…

Through her work, EJ throws traditional notions of disability into question by showing us the beau-ty of the brain, any brain. Her work helps us shift our assumptions about disability and move closer to those with different brain diseases. She tells us: “The more disabled I become, the more I am fas-cinated by what I can do to enlighten the world.”

Co-creating language

As we have demonstrated, the language of Social Construction — relationality, dialogue, con-versation — is embroidered into our exchanges with EJ. We enter into different worlds, weaving multiple voices. Berland (2008) echoes the importance of how we talk with each other and the effect it can have. “It’s how you ask the question” and how it can invite the patient’s voice:

EJ: Becoming elderly is gradual loss of the body… is fascinating and awful.

Approach patients with curiosity, honor, honor.

We create a vocabulary as we engage in dialogue. We use EJ’s words, or those that emerge during our conversation. We are struck by her words and by how they open new spaces of meaning — words like sacred space, acknowledgement, curiosity, honor; also visible, invisible, interesting, fasci-nating, transformation, tribe, community.

Q: How would you like to be called–patient, community member, participant?

EJ: I’m fascinated…

I like considering myself as a member of a tribe…

of spinal cord injury or chronic illness…

being part of a community…

Reflections and Implications

EJ’s work brings to mind a series of interconnected moments: in waiting rooms, with participants who complete her conversation cards; who wait in line to speak to her after her talks; making her art available for further discussion and reflection — in museums, academic buildings, neurology waiting rooms’ etc.

In this chapter we have introduced an exemplar that is constitutive of the process of dialogue, rela-tionality and social poetics as a practice of social construction by recalling moments that matter, creating new possibilities of practice. To be struck by events in this way is to be moved by them, to be guided by them and called to action. Here, we have enacted this process, noticing when we are moved, articulating it in dialogue, making visible what matters, then carrying it over into practice. This iterative, reflecting process, which we have termed a social poetics, (Katz and Shotter, 1996) consists of noticing a series of inter-related moments, their context and how they matter to the other participants, thus making them available for further dialogue and reflection and carrying them over as a practice resource for a wider community.

We privilege the voices of patients, community members, who are often unheard or silenced and notice how new possibilities of meaning emerge. We are moved by EJ’s experience, by how she has developed new capacity for engagement that allow her and others with disabilities to carry on with their lives. This exemplar captures and resonates with social constructionism in how dialogue and poetics can create new practices, with our emphasis on participatory practice and our shared focus on possibility and creating meaning in ‘relational exchange’ (Wasserman and McNamee, 2010; McNamee interview, Gergen, 2009).

References

Berger, J. (2001) “The hour of poetry,” in John Berger Selected Essays, G.Dyer (Ed.), NY:Pantheon.

Berland, G. and Buckwalter, G. (2008) NPR Interview with Gretchen Berland and Galen Buckwalter on video recording and revelations about interactions between physicians and patients with disabilities. NEJM Audio Interview, doi:10.1056/NEJMdo002136.

Berland, G. “The View from the Other Side: patients, doctors and the power of a camera”, doi:10.1056/NEJMdo002136, December 20, 2007.

Cavell, S. (1996) “Comments on Veena Das’s Essay ‘Language and Body: Transaction in the Constructions of Pain’,” Dædalus, 125 (1), pp. 93-98.

Chodosh, S. and Tormes, L. (2016) “The Art of Neuroscience”, Scientific American, in SA Mind 27,6, 52-56. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind1116-52.

Das, V. (1998) “Language and the Body: Transactions in the Construction of Pain,” Dædalus, 125 (1), 67-92.

Gergen, K.J. (2009) Relational being: beyond self and community, NY: Oxford University Books.

Jameson, E. (2018) “I wish my healthcare provider knew…” thebmjopinion, January 22, 2018.

Jameson, E. (2018) “Dreaming of a Prettier Chair”, New Mobility, April 2, 2018.

Jameson, E. (2019) “Imperfect Life Art Show at KECK School of Medicine at USC,” April 17, 2019 “https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6S9nDWgmqr4”.

Katz, J. (1984) The Silent World of Doctor and Patient, NY:The Free Press.

Katz, A.M., and Alegria, M. (2009) “The Clinical Encounter as Local Moral World Shifts of Assumptions and Transformations in Relational Context,” Social Science and Medicine 68: pp. 1238–1246.

Katz, A.M., Conant, L., Inui, T., Baron, D. and Bor, D. (2000) “A Council of Elders: Creating a Multi-Voiced Dialogue in a Community of Care,” Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 50(6), 2, pp. 851-860.

Katz, A.M., & Shotter, J. (1996) “Hearing the Patient’s ‘Voice’: Toward a Social Poetics in Diagnostic Inter-views,” Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 43, No. 6, pp. 919-931.

Kleinman, A. (1995) Writing at the Margin: Discourse between Anthropology and Medicine, Berkeley: U.Cal. Press.

Kleinman, A. (2012) “The art of medicine: Caregiving as moral experience”, The Lancet, Vol. 380, November 3, 2012, pp.1550-1551.

Kleinman, A. (2015) The Art of Medicine, “Care: in search of a health agenda”, The Lancet, Vol. 386, July 18, 2017, pp. 240-241.

Radley, A. and Bell, S.E., (2011) “Another way of knowing: Art, disease and illness experience,” Health, 15(3), pp.219-222.

Vilela e Souza, L, Santos, MA, Medonca Corradi-Webster, C., Guaneas, C., Moscheta, M. (2010) “Social Con-struction and Health: An interview with Sheila McNamee”, Universitas Psychologica, vol 9(2), pp.574-584.

Wasserman, IC and McNamee, S. (2010) “Promoting compassionate care with the older people: a relational imperative,” International Journal of Older People Nursing, 5, pp. 309-316.

Wittgenstein, L.W. (1953) Philosophical Investigations, Oxford: Blackwell.

English translation of Bruno Tapia Naranjo